“Life, Love, and the Literary: Cultural Power and Prestige in Renaissance Marriage Chests”

In September 2018, I was asked by the Chazen Museum of Art to give a talk in honor of their exhibit, “Life, Love, and Marriage in Renaissance Italy.”

From the Chazen website: “Organized by the Museo Stibbert and Contemporanea Progetti in Florence, Italy, the Chazen Museum of Art will host an exhibition of Italian wedding chests, also known as cassoni. To explore the social and practical functions of these important objects, the exhibition will include related domestic items such as maiolica wares, fabric, and architectural decorations, in addition to panel paintings and intact chests made in Italy from the 14th to the 16th centuries.”

I was given free rein in terms of content for the talk itself, which was a bit nerve-wracking at first. I’m not an art historian by training, and my own research focuses on the literature of the Italian Renaissance, rather than the art — so I decided to combine the two. The end result: “Life, Love, and the Literary: Cultural Power and Prestige in Renaissance Marriage Chests.”

Interested? Keep reading for the full text of my talk from September 27, 2018.

LIFE, LOVE, AND THE LITERARY

There are some folks in the audience this evening that have dedicated their entire careers to the study of the time period that we call the Renaissance, and there are likely others who have heard of this era perhaps only in passing. Given that potential disparity, I’d like to begin my talk tonight with some of the basics:

What is the Renaissance? Or rather, why do we call it that? When asked that question, people tend to respond with the literal definition of the term “Renaissance” — a French word meaning “rebirth.”

“But what was reborn?” I might counter. Literature, the Visual Arts? We know that there was great artistic output during the Italian Middle Ages (let us recall the great medieval painter, Giotto, for example) and there certainly was Literature — one only need think of Dante’s masterpiece, The Divine Comedy, to disprove any notion that the Middle Ages were “Dark,” as some have called them. Perhaps it is better, then, to refer to the Renaissance— a time period beginning roughly around the close of the 14th century — as an era of rediscovery: a rediscovery of classical antiquity as the epitome of culture and values, which foregrounded Greek and Roman models of art, architecture, philosophy, and literature, and moved beyond a strict focus on the afterlife that generally defined Medieval cultural production.

In Italy, the Renaissance was not only an era of rediscovery of classical antiquity but was also the birth of an era of individualism that gave rise to the intellectual orientation that we now call Humanism. Humanism is a primarily intellectual philosophy that gives principal importance to human, rather than divine, matters — a significant break with the intellectual and philosophical tradition of the Middle Ages. During the Renaissance, this manifested in a revived interest in ancient Greek and Roman thought, and inspired more than two centuries of artistic, intellectual, and literary works. We are currently surrounded, in this very gallery, by some of the products of that revival.

And it is no coincidence that a great number of items in this exhibit are Florentine—indeed, it was the city of Florence where Renaissance humanism was born and first practiced, and the city from which humanistic endeavors were exported throughout Italy, and indeed throughout Europe, for much of the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries.

My talk this evening will eventually settle on a very specific, material output of the Renaissance —marriage chests, or cassoni in Italian. These items were, to quote the opening panel of this exhibit, “objects that best represented the political, social, economic, religious, and artistic dynamics at play during the Italian Renaissance,” and the exploring these intersections will hopefully provide fruitful ground for discussion this evening. But before we jump in, it could be useful to discuss the context in which they were created, that is, the structure and organization of Renaissance Florentine society.

Florence was, and remains to this day, a small city (today, it has approximately 380,000 residents, just slightly larger than the city of Madison). During the 15th century, it was home to a population of approximately 60,000 Florentines, who were divided into four main social classes: the nobility, the merchants (such as those in the wool, silk, or cloth trade), the tradesmen (such as butchers, tanners, smiths, cooks, stonemasons, innkeepers, tailors, and bakers), and the unskilled workers (like those who worked as spinners, weavers, and dyers), who did not belong to a guild at all and could not, by law, form one.

Constitutionally, Florence was an independent republic, and theoretically, every member of the city’s guilds, or Arti, had a say in its government, but this was far from being the case in practice. There were twenty-one in all, with seven major guilds and fourteen minor. A hierarchy existed among the major guilds as well, where that of the lawyers, L’Arte dei Giudici e Notai, boasted the highest prestige, followed by the wool, silk, and cloth merchants, belonging to the three Arte della Lana, Arte di Por Santa Maria, and Arte di Calimala. The government of Florence was formed by the eligible members of these twenty-one guilds: men aged 30 and over (who were not known to be in debt and who had not served a recent term, nor were related to someone who had) would enter their name to be drawn from eight leather bags, one for each of the available positions. The men selected became known as Priori and would serve in the government known as the Signoria, with terms that lasted a mere two months—a term limit that we all might appreciate these days.

It is important to remember that Florence was also a city plagued by factional strife — warring families with competing interests — and also a city under constant threat from outside invaders: the French monarchy in the North and the Spanish kingdom that controlled the South. Its growing merchant class made it a very wealthy city, but at this time in history, wealth did not necessarily equal prestige nor status. A wealthy merchant could not, for example, simply ‘earn’ status as a noble, even if he became the city’s richest man. Yet money could still buy power, as we can see in the case of the House of Medici, an Italian banking family turned political dynasty. This family’s fortune began in the 14th century, prospering in the textile trade guided by the wool guild of Florence, the Arte della Lana (one of those seven major guilds). By the late 14th century, under Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici (1360-1429), the family’s financial success allowed for the creation of the Medici Bank, which in turn bought them political power and influence in the Florentine government. Yet the Medici family would always be considered what we today might call “New Money” by the Florentine nobility, and aristocratic families such as the Pazzi, the Albizi, and the Strozzi, did not peacefully accept the Medici’s claim to power.

Now, it became very much in the best interest of the Medici family to project an image of power and benevolence, particularly under the leadership of the paterfamilias (or, patriarch of the family), Cosimo di Giovanni de’ Medici (1389-1464), who understood that popular support could bolster any claims to power that his family wished to exert. The emergence of Medici rule and the image of the Medici as aristocrats (although they lacked this pedigree in official terms) can be seen as the result of a conscious plan that began during the reign of Cosimo, who commissioned artwork and buildings for the purpose of imprinting his image and his family’s name on the city of Florence — or in modern terms, what we might call “brand recognition.” To this end, Cosimo also heavily patronized public festivals — so much so that these events became symbolically linked with the family’s name. Cosimo also sought to mold his grandson, Lorenzo, in his image in order to preserve Medici power and influence and continue it into the next generation.

Born in 1449, Lorenzo de’ Mediciwas destined to become the future face of the Medici family, and learned well from his grandfather the political power that patronage of the arts could provide. Indeed, Lorenzo would come to see art and literature, in particular, as a political tool —one of many means by which he could control his image and that of his family. He also knew how powerful the arts could be as a self-fashioning tool: while Lorenzo sought to maintain the aspect of a public servant that did not seek power, he simultaneously constructed himself in the image of a prince. In fact, today, Lorenzo de’ Medici is more popularly known by his nickname: Lorenzo il Magnifico—Lorenzo the Magnificent.

Throughout his lifetime, it is clear that he knew how to use art and literature both as cultural capital and as propaganda. He was well aware of Florence’s precarious position, geographically and politically, and actively used patronage of the arts to raise the cultural prestige of his city throughout Italy. He intentionally engaged with philosophers, writers, and artists, and purposefully commissioned many great works so that one might be able to say, “This. This came from Florence.” Thus it is not merely a happy coincidence that some of the Italian Renaissance’s greatest names — Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Sandro Botticelli — came from the city of Florence. During this time, an artist needed a patron, or he was just simply out of work. Lorenzo the Magnificent was more than ready to fill that role. He had the financial means and the political goals. He also was a great patron of literature, which was one of the most powerful tools of propaganda available to him—perhaps more so than in painting, sculpture, or architecture. The scholar and poet Angelo Poliziano, for example, was commissioned to compose a poem in honor of the joust by Lorenzo’s younger brother, Giuliano, as Lorenzo knew that the pageantry and spectacle of the joust, which both celebrated his brother and honored the family name, would be ephemeral if not immortalized in poetry. Such poetry continued the image-making process, as Poliziano employed well-recognized literary conventions (pastoralism, the courtly love tradition, Neoplatonism) in order to paint a picture that invited Florentines to associate the Medici with gods.

Lorenzo had hosted his own joust just six years prior, an event filled both splendor and symbolism. Wealth, pageantry, courtly tradition, and feudal combat all combined at this event to imbue Lorenzo, as the head of the Medici family, with an aura of majesty and power. At this joust, which took place on February 7, 1469, his standard (a sort of banner that served as a personal emblem to an individual or family, often used in battle) was painted by the master Florentine painter Andrea del Verrocchio and bore pictures of laurel branches and the French motto Le Temps Revient (“time renews itself”). This standard, which would have flown high for all to see, was full of symbolism: Lorenzo’s very name quite happily coincided with the evergreen laurel tree associated with the poet Petrarch’s love, Laura (laurel in Italian is lauro, so Laura-lauro). The laurel was also the symbol of the god Apollo, who was the son of Zeus and the god of, among other things, music, poetry, truth, healing, light, and the sun. Lorenzo was all too keen to appropriate these symbols as his own. Furthermore, the motto Le Temps Revient bore a connection to the Roman poet Virgil’s Eclogues, which had predicted a return of the ancient Golden Age.

All these symbols would have been well-recognized by the Florentines present at the joust, and the message could not have been clearer: in a world of inconstancy, Lorenzo and the Medici family are a constant, like the evergreen laurel; they promise peace and renewal to Florence and her citizens.

Now what does this have to do with marriage chests? We are getting there! It is important to note that marriage was another means by which the Medici (and of course, powerful families in general) strengthened their social and political position. Lorenzo’s joust in February 1469 was, in fact, arranged to celebrate his betrothal to Clarice Orsini. Now, this particular arranged marriage was a departure from the Medici family’s traditional policy of choosing a bride from within the circle of great Florentine families, which would have insured and fortified internal alliances. However, Lorenzo’s father, Piero, recognized the importance of having external support from the powerful families beyond Florence, and as such, sought to forge a dynastic alliance with the Orsini, one of the oldest, noblest, and most powerful families in Italy. The Orsini had great influence in the kingdom of Naples, and even more power in Rome. Importantly, they were also a family of soldiers: an alliance could provide the Medici with an armed force in case of need. Piero also knew that choosing a bride from one Florentine family risked incurring the jealousy of the other families, potentially destabilizing an already volatile political climate.

Notably, the historical record shows that Clarice Orsini’s dowry was fairly small. Her family believed that the alliance itself was honor enough for the Medici, and that they were in no position to make further (monetary) demands. Interestingly, the tables would turn twenty years later, when Lorenzo and Clarice’s son, Piero di Lorenzo de’ Medici became betrothed to another Orsini daughter. Lorenzo’s power and influence had increased exponentially in these intervening years, and it was now understood by the most powerful families in Italy that a marriage with a Medici son would establish an alliance of the utmost value; they were now proud to align themselves with a family that was only just barely less than royalty (relevant side note: Giovanni, Piero’s brother and Lorenzo’s second son, would later become Pope). The dowry brought to Piero by Alphonsina Orsini was double that of Piero’s mother, Clarice.

Returning to Lorenzo: the festivities in honor of Lorenzo and Clarice’s marriage took place in June 1469 and were certainly extravagant. In-kind gifts — capons, hens, wax, wine, sweetmeats — were sent in from all over Tuscany to supply the 800-guest banquet. The celebrations lasted several days, and were held in accordance with Florentine tradition. Inventories record that Lorenzo’s own bedchamber contained three chests (one cassone and two forzieri)—two of which were painted with scenes from Petrarch’s Triumphs (a series of poems in the Tuscan language evoking the Roman ceremony of triumph, where victorious generals and their armies were lead in procession by the captives and spoils they had taken in war). Again, we see how Lorenzo utilized literature — in this case, Petrarch’s poetry — to evoke, and maintain, an aura of power and prestige.

Now, it is not to my knowledge that any of the pieces with us here today, in this gallery, belonged to the Medici family, but the point that I would like to convey is this: they certainly could have. Because if we look around at the examples in this room, the panels here, which were taken from marriage chests, are just as replete with symbolism as Lorenzo’s standard on the day of his joust in 1469 or as depicted in the painted scenes on his pair of chests. The families that commissioned these utilitarian works of art sought the same goals as the Medici family. They wanted to convey specific messages, of power and prestige, of moral teachings and marital virtues, of family history and honor—and to this end, the value and function of the marriage chest during this period played an important role.

Marriage chests were a part of the general commodification of marriage in 15th-century Florence—this item was part of the financial exchange made between families in order to achieve a marriage alliance. These chests also had a public function as well, in the role that they played in the often lengthy and complex series of marriage rites that were practiced at this time. They were made of wood (the quality of which would have varied according to means), were rectangular in shape and about two meters in length. They would have been decorated, typically with painted panels as we see in the examples in this gallery. After its commission, the chest would have been taken in a public and ostentatious procession of the bride to her new home and would have been on display for all to observe.

The wedding chest was not only the most important piece of furniture for storing everyday items for all classes of society — they were kept in private homes after the nuptials of the bride and groom, and would be filled with the family’s personal possessions, such as clothing, linens, and other important personal items — but they also held an important symbolic matrimonial function. As I mentioned at the very beginning of this talk, marriage chests served as an important and elaborate symbol — of wealth, of prestige, of status — and were those objects that best represented the intersections of the political, social, economic, religious, and artistic dynamics at play during this time period. An important question to explore, then, would be: How did literature, and the narrative scenes chosen to decorate these chests, further the objectives of the families who commissioned them? That is, what do wealth, prestige, and literature have to do with one another?

References to literature, both classical and Italian, through the depiction of narratives in the panel paintings allowed the family to display their cultural legitimacy in order to cement a certain prestige and status for the family beyond mere wealth. Of course, this attitude toward the cultural power and prestige of literature was made possible by a set of cultural norms in play: the veneration of antiquity, a confidence in the value of education, and an emphasis on literary credentials in the process of constructing individual, professional, or family honor. Certainly, the ornate nature of the decorations was an overt symbol of wealth in itself, but it is important to recall, for example, the purposeful attempts by the Medici family to establish a certain cultural prestige in order to solidify the status of the family among the aristocratic class from which it was excluded. Lorenzo de’ Medici sought to accomplish this, as we explored, through his close connection to and patronage of the literary and cultural elite of Florence. This connection to culture, and literature in particular, was about making important social connections as a tool of self-fashioning and reputation-building: even the most complex exchanges among the literary elite were as much social and involved with the search for distinction as they were scholarly. In this sense, expressions of humanism embodied in works of art were a powerful message in themselves.

Families that commissioned such marriage chests were not ‘humanists’ per se (that is, they were not necessarily actively seeking humanistic pursuits in a traditional sense) — rather, they were seeking to obtain a measure of honor that connected to educational and literary attainment that had the power to reshape self-perception, reputation, and even the social position of the family—in a sense, a measure of honor that we can define as “cultural legitimacy” (a term I borrow from Sarah Gwyneth Ross). In this sense, there existed an “aristocracy of culture” — Lorenzo de’ Medici recognized this and used it to his advantage and he sought to cultivate this particular image for himself and his family. Access to the literary created possibilities for joining a cultural lineage, one which had become so valued in Renaissance culture as part of the “rediscovery” of classical antiquity. It was, in a sense, also the recognition of an Italian cultural heritage that had a connection to and roots in Greco-Roman civilization.

Of course, the decoration of these marriage chests often conveyed moral content as well, derived from allegorical, mythological, or biblical examples. These stories were chosen for their didactic function as well as for their symbolism: certain stories would serve as a reminder, for example, to brides of the virtues they were expected to extol.

To our right, we have a panel from a marriage chest painted by Giovanni di Ser Giovanni Guidi featuring the story of Lisabetta di Messina, which is a novella from Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron — an excellent example of this sort of didactic narrative material.

In brief, Lisabetta is a young, beautiful, and educated girl who lives in Messina (a city in Sicily) with her three brothers, wealthy merchants who have inherited all their father’s estate. Lisabetta falls in love with one of the family’s employees, the handsome Lorenzo from Pisa. Before long, Lisabetta’s brothers learn of their romance and decide to take drastic action: they lure Lorenzo to the countryside with promises of a business affair and murder him. They return without him, naturally, and tell Lisabetta that he has been sent away to deal with a business matter. Lisabetta despairs in his absence, until Lorenzo visits her in a dream with torn and rotting clothes, alluding to his decomposition, and tells her where to locate his body. Lisabetta finds Lorenzo’s body, then cuts off his head, wraps it in a beautiful cloth, and gives it a loving burial. She plants basil in the pot over Lorenzo’s head, and waters it every day with perfumed water and her own tears. The brothers take notice of her strange, obsessive behavior and decide to investigate, finding the head inside the basil pot. They panic, re-bury Lorenzo’s head, and flee Messina to Naples, lest their crime be discovered. The tale concludes as Lisabetta cries herself to death, literally, over the loss of the basil pot. As we can see from the two panels that feature this narrative, we have a scene depicting the three brothers luring Lorenzo out of the city, and another depicting Lisabetta in mourning. For as gruesome as this tale is, it is meant to represent unconditional love—Lisabetta never stops loving Lorenzo, and cares for him (his head) even in death. Interestingly, no other depictions of this story are known to exist, although tales taken from Boccaccio’s Decameron were a popular content choice for marriage chests because they were highly recognizable in Florentine society — meaning that the lessons imparted would have been easily conveyed.

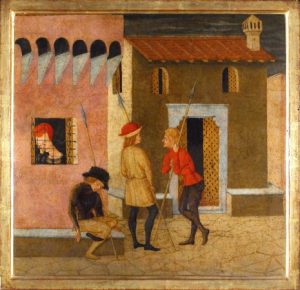

As we can see from the items in this gallery, another popular choice for narrative scenes comes from the classical tradition—Homer, Virgil, and Ovid, for example. This is largely connected to that spirit of renewed interest in classical antiquity, and in particular, a renewed reverence for classical literature. In this exhibition, we have a panel by Apollonio di Giovanni di Tomaso that depicts the well-known story of Apollo and Daphne from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. In Greek mythology, Apollo was an important but boastful god (we might recall him as a favorite of Lorenzo de’ Medici — also known as the god of music, truth, light, and reason; all important aspects to Renaissance culture), who, one day, mocked Cupid, the god of Love, for his use of a bow and arrow, a weapon far more suited to a powerful god such as himself. Offended, Cupid decides to show Apollo exactly what he is capable of with his bow and arrow, piercing him with his golden arrow of love, intending for the boastful god to fall in love with the beautiful nymph Daphne. But as part of his revenge, Cupid also strikes Daphne with a lead-tipped arrow that causes her to reject Apollo’s love. It all works according to plan: Apollo sees Daphne and falls madly in love; Daphne, having always avoided love in the first place as she preferred to devote herself to hunting, flees from Apollo. She arrives at the River Peneus and calls upon her father, the river god, to help her change her form; she is transformed into a laurel tree before Apollo could capture her. Still in love, Apollo decides to transform the laurel tree into an evergreen and to adopt it as one of his sacred symbols, adorning his head, his lyre, and his bow with laurel. As Apollo himself prophesies in the tale, over the centuries this myth would transform into custom, and wreaths of laurel were used to honor winners, warriors, and poets over the course of history. We can recall that Lorenzo de’ Medici himself had adopted this very tradition as part of his own image. This popular story was a frequent choice for marriage chests: Daphne was considered a positive example of chastity and Apollo is a symbol of both power and eternal love.

Even today, the symbols we choose for ourselves carry a powerful message. Our clothes, our flags, our mascots, even our tattoos, are part of the story we seek to tell about ourselves. It was no different during the Renaissance, and the important function of the marriage chest played a big role in that messaging. Whether we focus on the cultural prestige, powerful symbolism, or didactic function conveyed by these items, it is clear that their significance, along with the other beautiful items in this exhibit, bears continued discussion even today, some six centuries later.