The Queen’s Not Mad, She’s Machiavellian

The hit HBO series Game of Thrones has captured the imagination and seized the attention of viewers around the world, and as the show progresses through its final season — only one episode remains! — loyal fans continue to voice a multitude of opinions on, and condemnations of, the eight-season narrative arc as it hurtles towards conclusion.

Season 8, Episode 5, “The Bells,” (aired 12 May 2019) seems to have left many fans frustrated, if not confused and even angry, about the choices made by the aspiring ruler of the Seven Kingdoms, Daenerys Targaryen, as she nearly single-handedly sacked King’s Landing on the back of her last remaining dragon [spoiler alert]. Despite her counsel’s explicit advice to the contrary, she sets the city ablaze, killing thousands of innocent bystanders / citizens / future subjects, seemingly in a fit of rage and vengeance. Think-pieces have been sprouting up all over the internet calling Daenerys everything from the “Mad Queen” (a reference to her late father’s nickname, the “Mad King”) to the more colloquial, and infuriatingly reductive, “Crazy Ex-Girlfriend.” Many commentators have blasted the show’s writers for “utterly failing” her character, transforming her into the spiteful and dangerous tyrant she had always claimed to abhor. The “Breaker of Chains” appears to have succumbed to a troublesome stereotype after all.

Yet perhaps Daenerys’ actions in King’s Landing were more strategy, less impulse, than meets the eye. I would like to offer a more nuanced take, based on my own research on Niccolò Machiavelli’s infamous 16th-century treatise, The Prince — if only to argue the point that (criticism within GoT fandom aside) Daenerys may have proven herself to be a shrewd disciple of Machiavellian politics yet, the female embodiment of natural-born (male) virtù. Stereotypes be damned.

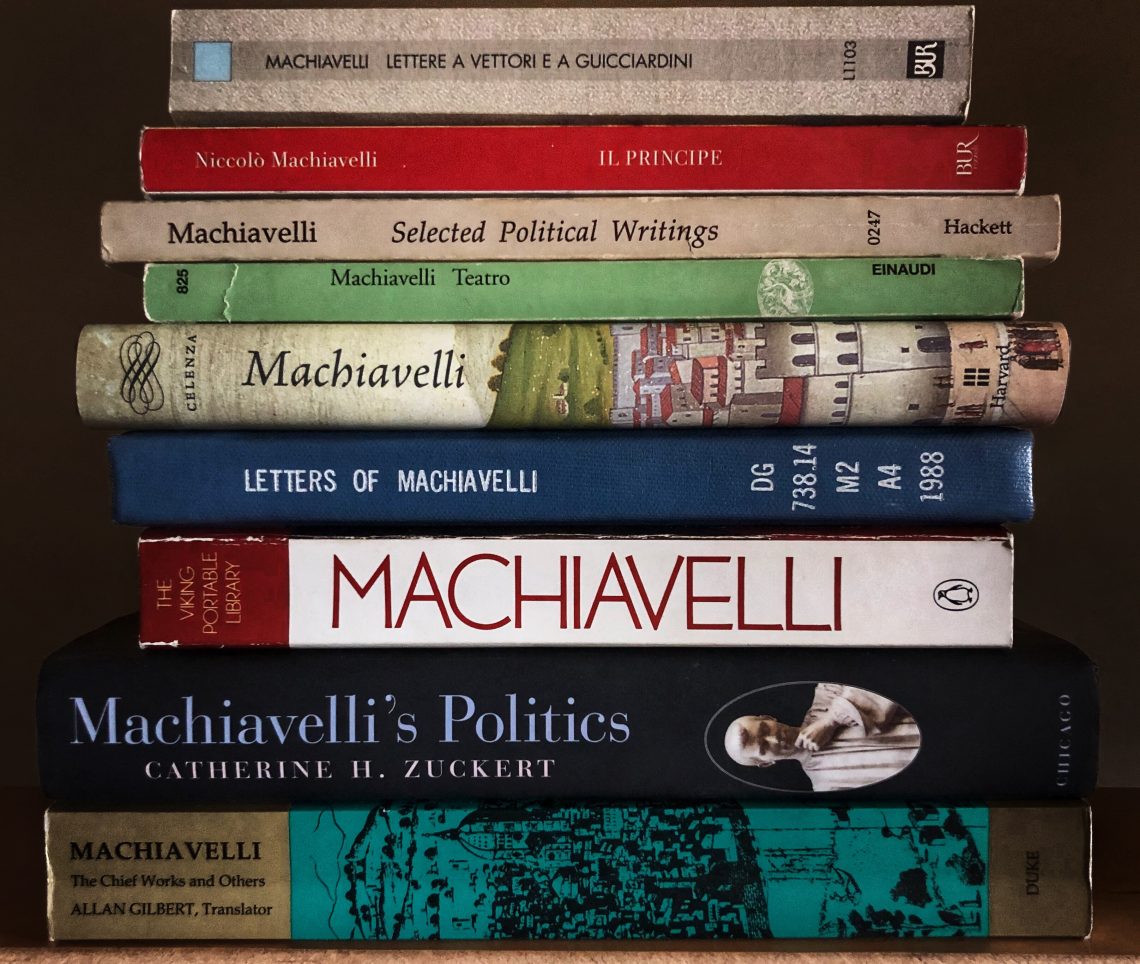

Written around the year 1513, Machiavelli composed his “little book,” known as a mirror-of-princes (a sort of treatise aimed at providing advice and instruction to would-be / soon-to-be princes), and dedicated it to Lorenzo de’ Medici the younger, a member of the powerful Medici family that ruled Florence during the Renaissance (for Italian history buffs — his grandfather was Lorenzo il Magnifico). Machiavelli’s intent in writing this particular work has been the subject of great debate across the ensuing centuries (in one hypothesis: having been exiled and banned from Florentine politics, was he now trying to get his job back by proving his keen political sensibilities?), but that remains beside the point here. Instead, I would like to focus on a series of passages from The Prince that I believe offer one key for understanding and interpreting the actions undertaken by Daenerys Targaryen as she makes her final push for control of the Iron Throne.

The first key lies in one of the early scenes of the episode, in which Jon Snow meets Daenerys for a final tête-à-tête before the strike on King’s Landing. Having already sensed Jon’s immense popularity and the loyalty he inspires across an impressive span of diverse groups and peoples within Westeros, she reveals her biggest insecurity, and thus vulnerability, related to her position as heir to the throne. Daenerys ultimately fears that a lack of love will transform into a lack of support for her rule, and so, in this meeting, she takes a stand on an issue that has remained one of the central questions in Machiavelli’s thought: is it better to be feared or loved?

Machiavelli offers his take on this question in The Prince, Chapter 17, “De crudelitate et pietate; et an sit melius amari quam timeri, vel e contra” [“On cruelty and compassion; and on whether it is better to be loved than feared, or the reverse”]. He acknowledges that certainly all rulers should want to be perceived as compassionate rather than cruel; yet at the same time, cruelty is useful. His primary example here, as elsewhere in The Prince, is Cesare Borgia, the illegitimate son of Pope Alexander VI who led the conquest of a number of Italian territories in order to expand his father’s [earthly] power. In Machiavelli’s view, Cesare’s reputation for cruelty and penchant for violent spectacle allowed him to unite territories, to restore order and peace. To further drive home the point, Machiavelli offers a counter-example as well, in which the people of Florence strove so intently to avoid the semblance of cruelty that it gave way to chaos in its conflict with Pistoia in 1501. Thus, for Machiavelli, cruelty is compassion, and vice-versa.

He continues: “This leads us to a question that is in dispute: Is it better to be loved than feared, or vice versa? My reply is one ought to be both loved and feared; but, since it is difficult to accomplish both at the same time, I maintain it is much safer to be feared than loved, if you have to do without one of the two. For of men one can, in general, say this: They are ungrateful, fickle, deceptive and deceiving, avoiders of danger, eager to gain.” *

“Nasce da questo una disputa, s’e’ gli è meglio essere amato che temuto o e converso. Rispondesi che si vorrebbe essere l’uno e l’altro; ma perché e’ gli è difficile accozzarli insieme, è molto più sicuro essere temuto che amato, quando si abbi a mancare dell’uno de’ dua. Perché degli uomini si può dire questo, generalmente, che sieno ingrati, volubili, simulatori e dissimulatori, fuggitori de’ pericoli, cupidi del guadagno.“

Indeed, Machiavelli had little patience for rulers who sought to act as the moral compass, as he explains in Chapter 15: “For the gap between how people actually behave and how they ought to behave is so great that anyone who ignores everyday reality in order to live up to an ideal will soon discover he has been taught how to destroy himself, not how to preserve himself.”

“Perché gli è tanto discosto da come si vive da come si dovrebbe vivere, che colui che lascia quello che si fa, per quello che si dovrebbe fare, impara più presto la ruin ache la preservazione sua.”

Thus, he continues, “It is necessary for a ruler, if he wants to hold on to power, to learn how not to be good, and to know when it is and when it is not necessary to use this knowledge.”

“Onde è necessario, volendosi uno principe mantenere, imparare a potere essere non buono e usarlo e non usarlo secondo la necessità.”

Daenerys encapsulates these very ideas in her parting words to Jon Snow. “Far more people in Westeros love you than love me,” she tells Jon. “I don’t have love here. I only have fear.” Jon replies by affirming his love and his loyalty as he declares, “You will always be my queen.” Daenerys approaches him and asks, slowly, quietly: “Is that all I am to you? Your queen?” She then tries to kiss Jon, but the emotional distance between them grows ever more palpable; he pulls away in silence as she steps back from him. The scene ends; “All right then,” she pronounces. “Let it be fear.”

It is as if, through Jon’s reaction, she sees her future kingdom recoiling from her too. It is this recognition — that fear is more powerful, more useful than love — that spurs Daenerys to her actions in King’s Landing. The second half of the episode, which follows the blazing trail of destruction around the city, focuses almost exclusively on that emotion. We even see, in a rare occurrence, Arya Stark succumb to that fear, a recognition of her own mortality and her desire to live, as she agrees to part ways with Sandor Clegane (The Hound) in order to survive the sacking.

Yet why does Daenerys choose to torch the city, street by street — effectively executing enemies and innocents alike? What is the purpose of striking that much fear? Machiavelli speaks at length on the need to eradicate the ruling classes as well as the surviving family of the former ruler when one acquires a new territory, though he makes no explicit mention of any need to eliminate the entire population as well. Nevertheless, Chapter 3 (“De principatibus mixtis” / “On mixed principalities”) offers one view of Daenerys’ thought-process; “There is a general rule to be noted here,” Machiavelli asserts. “People should either be caressed or crushed. If you do them minor damage, they will get their revenge; but if you cripple them there is nothing they can do. If you need to injure someone, do it in such a way that you do not have to fear their vengeance.” She chooses to crush.

“Per che si ha a notare che gli uomini si debbono o vezzeggiare o spegnere: perché si vendicano dele leggieri offese, delle gravi non possono; sì che la offesa che si fa all’uomo debbe essere in modo che la non tema la vendetta.”

Before leaving for King’s Landing, Daenerys herself had warned that her objective was not to protect the citizens of Westeros, but rather to create a better world for future generations; she tells Tyrion, “Mercy is our strength; our mercy toward future generations who will never be held hostage by a tyrant.” Machiavelli too would have seen mercy in violence, compassion in cruelty. This philosophy remains the primary motivation behind his notoriety as an “evil genius,” a reputation that has followed him throughout the centuries and continues to color reception and interpretation of his works even today.

Another significant passage, one that perhaps has most contributed to Machiavelli’s negative reputation, sheds further light on Daenerys’ strategy and echoes her words on mercy. In Chapter 8 (“De his qui per scelera ad principatum pervenere” / “Of those who came to power through wicked action”), he explores the idea of a purposeful cruelty: “I think here we have to distinguish between cruelty well used and cruelty abused. Well-used cruelty (if one can speak well of evil) one may call those atrocities that are committed at a stroke, in order to secure one’s power, and are then not repeated, rather every effort is made to ensure one’s subjects benefit in the long run. […] Those who use cruelty well may indeed find both God and their subjects are prepared to let bygones be bygones […]; those who abuse it cannot hope to retain power indefinitely.” Again, one episode in the series remains, and so only time will tell if the sack of King’s Landing constitutes cruelty well-used or cruelty abused.

“Credo che questo avvenga da le crudeltà male usate o bene usate. Bene usate si possono chiamare quelle — se del male è lecito dire bene — che si fanno a uno tratto per la necessità dello assicurarsi: e di poi non vi si insiste dentro, ma si convertono in più utilità de’ sudditi che si può. Coloro che osservono el primo modo, possono con Dio e con li uomini avere allo stato loro qualche rimedio […]; quegli altri è impossibile si mantenghino.”

I will conclude here with the story of another tyrant, Agathocles of Syracuse, who ruled Sicily from 317 BCE to 289 BCE, and whose story Machiavelli recounts in the same Chapter 8. Having originally been granted the power to rule by his fellow citizens, Agathocles soon turned to extreme, sustained violence in order to solidify his reign and wipe out any potential threats or resistance. In retaining absolute control of Sicily, Agathocles proved successful, and ruled until his natural death.

Yet in telling this story, Machiavelli makes it a point to clarify the terms of such success, further complicating the issue of power: “One ought not, of course to call it virtù [in Machiavellian terms, cunning or manly strength] to massacre one’s fellow citizens, to betray one’s friends, to break one’s word, to be without mercy and without religion. By such means one can acquire power, but not glory.”

“Non si può ancora chiamare virtù ammazzare e’ suoi cittadini, tradire gli amici, essere sanza fede, sanza pietà, sanza religione: e’ quali modi possono fare acquistare imperio, ma non gloria.”

When the Queen ultimately chooses fear, she may be aware that she denies herself glory, too. She cannot have love, she cannot have glory, so fear and power it is. Yet that does not make her “mad.”

Only quintessentially Machiavellian.

.

* Translation by David Wootton, Machiavelli: Selected Political Writings (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, Inc., 1994).

Italian text from the grandi classici BUR edition: Niccolò Machiavelli, Il Principe, ed. Martina Di Febo (Milano: BUR, 2013).